- Home

- Zhongshu Qian

Humans, Beasts, and Ghosts Page 4

Humans, Beasts, and Ghosts Read online

Page 4

9. Edward M. Gunn Jr., Unwelcome Muse: Chinese Literature in Shanghai and Peking, 1937–1945 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1980), 9.

10. Jos. Schyns et al., 1500 Modern Chinese Novels and Plays (1948; repr., Hong Kong: Lung Men Bookstore, 1966), 163.

11. Huters, Qian Zhongshu, 78–79, 70–95 passim.

12. Qian Zhongshu, Limited Views: Essays on Ideas and Letters, ed. and trans. Ronald Egan (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998), 137. See Egan’s insightful analysis of Qian’s practice of “striking a connection” (datong ) (15–22 passim).

13. Ibid., 138.

14. “God’s Dream,” in which the authorlike Creator dreams of inadvertently destroying his creations (man and woman) after discovering that they have stopped obeying his will, has inspired at least one productive reading along these lines, though it stops short of branding Qian a postmodernist. See Sheng-Tai Chang, “Reading Qian Zhongshu’s ‘God’s Dream’ as a Postmodern Text,” Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews 16 (1994): 93–110.

15. In a one-line preface to the series, which began in vol. 1, no. 3 of Criticism Today (Jinri pinglun ) (January 15, 1939), Qian explained: “‘Cold’ because the room I’m renting is freezing; ‘jottings’ because I let my pen wander freely. That’s the truth, and that’s my preface” (14). Zhang Wenjiang , one of Qian’s biographers, hypothesizes that “cold” implies “to take a detached point of view” (literally, “to watch cold-eyed from the sidelines” [lengyan pangguan ]). See Zhang Wenjiang, Wenhua kunlun (Cultural Giant: A Biography of Qian Zhongshu) (Taipei: Yeqiang, 1993), 56.

16. For more on the “discrete observation,” see Ronald Egan, “Introduction,” in Qian, Limited Views, 1–26.

17. Hsia, History of Modern Chinese Fiction, 437.

18. See, for example, Ingrid A. R. De Smet, Menippean Satire and the Republic of Letters, 1581–1655 (Geneva: Droz, 1996); Howard D. Weinbrot, Menippean Satire Reconsidered: From Antiquity to the Eighteenth Century (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005); and W. Scott Blanchard, Scholars’ Bedlam: Menippean Satire in the Renaissance (London: Associated University Presses, 1995).

19. Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1971), 230–31, 309.

20. Blanchard, Scholars’ Bedlam, 12.

21. For an insightful discussion of the “nonsense-making method” (chedan fa ) that Qian employs in Margins, see Huters, Qian Zhongshu, 79–95 passim.

22. The 2001 edition was published in traditional Chinese characters; in 2002, Sanlian published a simplified-character version of the collection, which corrected some, but not all, the errors introduced in the 2001 edition. Most subsequent reprints have been based on the 2002 edition.

23. For a detailed, if idiosyncratic, study of edition issues up to the 1990 Chinese Academy of Social Sciences edition of Written in the Margins of Life, see Wang Ziping , “‘Xie zai rensheng bianshang’ banben kao” (Edition Research on Written in the Margins of Life), in Liaodong Miusi zhi hun: Qian Zhongshu de wenxue shijie (Stirring the Muses: The Literary World of Qian Zhongshu), ed. Xin Guangwei and Li Hongyan , 85–106, Qian Zhongshu yanjiu congshu (Collected Studies on Qian Zhongshu) (Shijiazhuang: Hebei jiaoyu chubanshe, 1995).

24. Ibid., 86.

25. Huters, Qian Zhongshu, 155.

26. To note just a few brief examples of derivativeness: In “The Devil Pays a Nighttime Visit to Mr. Qian Zhongshu,” the Devil remarks, “At art exhibitions I talk about connoisseurship and at banquets I talk about the culinary arts. But that’s not all. Sometimes I instead talk politics with scientists and art with archaeologists; after all, they don’t understand a word I say and I’m happy to let them pass off my phrases as their own.” In “Reading Aesop’s Fables” Qian repeats this pattern: “A bat pretends to be a crow when he encounters a crow and pretends to be a land animal when he encounters a land animal. Man, being much smarter than a bat, employs the bat’s method conversely. . . . He parades refinement before soldiers and plays the hero to men of letters. Among the upper classes he is a poor and tough commoner, but among common people he becomes a condescending man of culture.” In “God’s Dream” God flashes a lightning smile from behind a cloud and issues thunderous laughter, repeating an allusion from “On Laughter.” Liang Yuchun (1906–1932) had also incorporated the old joke about Plato and the plucked chicken into one of his essays over a decade before Qian used it in “A Prejudice.” See Liang Yuchun, “Zui zhong meng hua (yi)” (Drunken Dream Talk [1], 1927), in Liang Yuchun sanwen ji (Collected Prose of Liang Yuchun), ed. Qin Xianci (Taipei: Hongfan shudian, 1979), 16.

27. Lin Yutang (1895–1976), founder of the humor magazine Analects Fortnightly (Lunyu banyuekan , 1932–1937), was a prominent, bilingual intellectual in both China and the United States during the 1930s and 1940s. He appears as a satirical target in “On Laughter,” “Cat” (as Yuan Youchun), and Fortress Besieged (which places his book My Country and My People on the bookshelf of a Westernized Shanghai businessman along such “other immortal classics” as the Bible and Teach Yourself Photography). “Cat” also contains caricatures of Zhou Zuoren, Shen Congwen, and Luo Longji, as noted in Huters, Qian Zhongshu, 113–14.

Written in the Margins of Life

AND

Human, Beast, Ghost

AUTHOR’S PREFACE TO THE 1983 EDITIONS OF

Written in the Margins of Life AND Human, Beast, Ghost

Since archaeologists began promoting tomb excavation, the withered bones of countless ancient dead people and other artifacts have been uncovered. Since modern literature became its own specialized field of research, the soon-to-wither or already-withered works of living writers have also been dug up and exposed. For some of us, our delight at having been dug up has caused us to overlook the danger of such exposure, since we don’t realize that it is by leaving his works buried that the author preserves his undeserved reputation. Should the author himself take the lead in the excavation work, the loss might well outstrip the gains, and “digging one’s own grave” will become a self-contradictory pun: to open the grave in which one’s works are buried is also to dig one’s authorial grave.

I wrote Written in the Margins of Life forty years ago and Human, Beast, Ghost thirty-six or thirty-seven years ago. Back then, I had yet to feel that my life was becoming increasingly cramped and marginalized, and my views on the difference between humans, beasts, and ghosts were uninformed and somewhat mechanical. After I finished writing Fortress Besieged, I made a few edits to those two volumes, but the edited versions then went missing, which goes to show that I’m not terribly fond of my old works. Four years ago, Comrade Chen Mengxiong, who specializes in digging up and opening literary graves, began selling me on the idea that the two books should be reprinted. He knew I didn’t have copies of the books handy and he took pains to make copies of the originals and mail them to me. When it comes to writing, I could be said to be a bit of a loafer who has “forgotten his origins,”1 because I’m too lazy to carefully preserve and collect my early publications. When an editorial committee was established for the Compendium of Shanghai Literature from the War Period, Comrades Zhu Wen and Yang Yousheng wanted the series to include these two books. I was confident that I had sufficient reasons to decline: Written in the Margins of Life was not written in Shanghai and Human, Beast, Ghost was not published during wartime, so to include them in this series would seem fraudulent. At that point, Comrade Ke Ling from the series editorial committee said to me: “If you don’t allow these books to be reprinted domestically you’re effectively allowing poorly edited ‘pirated editions’ to continue circulating overseas. That’s irresponsible. The editorial committee has its own reasons for wanting to include these works in the series, so don’t worry yourself on our behalf.” He spoke convincingly and volubly, and as I’ve always gone along with my old friend’s suggestions, there was nothing for me to do but to give my consent. I had to bother Comrade Mengxiong to furnish me another copy of the

works, since I had long ago lost the copies he had mailed me earlier.

I bit the bullet and reread these two books, limiting myself to only a few minor edits. As these books had pretty much already transformed into historical materials, I was not at liberty to make deletions and additions as I saw fit or to flat out rewrite them. But, as they were, after all, in my name, I still reserved some sovereign rights, so I took the liberty of making a few piecemeal cuts and minor enhancements.

The format of the series called for each author to write a preface recounting his writing process and his works’ circumstances of authorship. During the actual process of creative writing our imaginations are often pitifully deficient, but when we come to reminisce about it later—be it several days or several decades later and whether we are reminiscing about ourselves or others—our imaginations suddenly become shockingly, delightfully, even frighteningly fruitful. I am a man of tepid ambition and am not interested in indulging in such creative reminiscing, so I simply will not bother sharing any memories or recollections. As these two books are not worthy of each having their own preface, this one will do for both.

August 1982

WRITTEN IN THE

MARGINS OF LIFE

DEDICATION

To Jikang

JUNE 20, 1941

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Several of the essays in this collection appeared previously in publications edited or prepared by Messrs. Sun Dayu, Dai Wangshu, Shen Congwen, and Sun Yutang.

Messrs. Chen Linrui and Li Jianwu reviewed the entire book and provided unstinting assistance in its printing and publication.

Since the author is residing deep in the interior at the moment, Ms. Yang Jiang, in Shanghai, selected, edited, and arranged these essays into one volume.

The author hopes that these individuals will not begrudge his trifling expression of gratitude.

PREFACE

Life, it’s been said, is one big book.

Should life indeed be so, most of us writers can only claim to be book critics. Possessing the book critic’s skill, we need not read more than a few pages to churn out a pile of commentary and wrap up a book review in no time.

Yet, another type of person exists in this world. These people believe that the purpose of reading a book is not actually to write a criticism or an introduction. Possessing the casualness and nonchalance of spare-time diversion seekers,1 they browse at their own leisurely pace. When an opinion strikes them, they jot down a few notes or write a question mark or exclamation mark in the blank margins of the book, akin to “eyebrow comments” in the top margins of old Chinese books or marginalia in foreign books. These piecemeal, spontaneous impressions do not constitute their verdict on the entire book, and having been written in passing they may contradict one another or go overboard. But the authors don’t bother about this. After all, for them it’s a diversion, unlike the book critic, who shoulders the weighty tasks of guiding the reader and chiding the author. Who has the ability and patience for such things?

If life is a big book, then the essays that follow can only be regarded as having been written in the margins of life. What a big book! It’s hard to read all at once, and even if the margins have been written on, there’s still plenty of blank space left.

February 18, 1939

THE DEVIL PAYS A NIGHTTIME VISIT TO MR. QIAN ZHONGSHU

“You and I should have met long ago,” he said, taking the chair closest to the brazier. “I’m the Devil. You’ve been tempted and tested by me before.”

“But you’re a conscientious fellow!” A sympathetic smile crossed his face as he spoke. “Even though you’ve fallen into my traps before, you haven’t recognized me. When you’ve succumbed to my temptations, you’ve only seen me as a lovable woman, a faithful friend, or a pursuable ideal. You’ve never been able to tell that it’s me. Only those who have been able to resist my temptations, such as Jesus Christ, have recognized me for who I am. But we were destined to meet today. A family was holding a commemorative vegetarian banquet involving sacrifices to spirits and ghosts, and they invited me to sit in the place of honor.1 I was tied up with that engagement for most of the evening and had a few too many drinks, so my vision got blurry, and while making my way back to my dark dwelling I entered your room by mistake. Electric lights in the interior provinces are a travesty—your house is as dark as Hell! But it’s colder here than where I live. There, sulfuric fires burn from morning to night, which of course would be unthinkable for you here—I hear the price of coal has gone up again.”

Recovering from my surprise, it occurred to me that I should fulfill my duty as host. I addressed my guest, “It’s an honor to receive your midnight visit. You darken my humble dwelling!2 I only regret that I’m the only one here to receive you, and I apologize for not having prepared a better welcome! Are you cold? Excuse me a moment while I wake the servant to prepare tea and add coal to the fire.”

“No need for that,” he said, staying me with the utmost politeness. “I can only sit for a minute, and then I’ll be on my way. Besides, let me tell you . . .” His expression became serious, yet intimate and sincere, like a patient reporting to his doctor that he is impotent, “. . . fire can’t warm me up anyway. When I was young I wreaked havoc in Heaven by trying to usurp God’s position. I didn’t succeed, however, and ended up being cast down to suffer in the frozen depths of Hell*—much like how in your mortal realm the Russian tyrant exiled members of the Revolutionary Party to the Siberian tundra. The cold air has driven all the warmth in my body into my heart, making me cold-blooded amid the heat.3 I once sat on a heated brick bed for three days and nights, but my bottom remained as cold as a pitch-black winter night . . .”

Surprised, I interrupted him, asking, “Didn’t Barbey d’Aurevilly also once say—”

“Yes,” he replied with a chuckle. “In the fifth story in Les Diaboliques he mentions my unwarmable bottom. This is why one abhors celebrity! As soon as you become famous you have no more secrets to speak of. All your private affairs get publicized by interviewers and reporters, and just like that you’re deprived of your material for an autobiography or a confessional.† Should I decide to write an account of myself in the future, I’ll have to make up some new facts.”

“Wouldn’t that run counter to the purpose of an autobiography?” I asked.

He laughed again. “I never imagined that your knowledge and insight would be as pedestrian as a newspaper editorial. This is the age of the new biographical literature. Writing biographies of others is also a type of self-expression, so there’s no reason not to insert your own views or write about others as a way of showing yourself off. Conversely, autobiographers invariably don’t have much of a ‘self ’ to write about, so they gratify themselves by rendering a likeness that their own wife and child wouldn’t recognize.4 Or they ramble on about irrelevant matters, noting the friends they’ve made and recounting anecdotes about other people. So if you want to learn about a person, you should read biographies he’s written of others, and if you want to learn about other people, you should read his autobiography. Autobiography is biography.”

I couldn’t help being impressed by this, and I inquired politely, “Would you permit me to quote that line of yours in the future?”

“Why not?” he replied. “Just be sure to use the formula ‘as my friend so-and-so says.’”

I was delighted, and replied modestly. “You think too well of me! Am I worthy to be your friend?”

His response dashed my hopes. “It’s not that I think well of you and am calling you my friend; it’s that you are attending to me and claiming that I’m your friend. When you quote the ancients in your writing, you should avoid using quotation marks to show that the words have been used before, but when you quote a contemporary, you always have to say ‘my friend’—this is the only way to solicit friends.”

Despite his frank talk, I plied him with a few more courtesies. “Many thanks for your excellent advice! I never expected you would also be

such a writing expert too. You already surprised and impressed me just now with your mention of Les Diaboliques.”

His reply was almost sympathetic. “No wonder other people say you can’t escape your class consciousness. You think I’m unworthy to read books, don’t you? I may be from the lowest stratum of society—Hell—but my aspirations have always aimed upward. I’ve done a fair amount of reading in my day, especially of popular magazines and brochures, and the like. That’s why Goethe praised my spirit of progress and my ability to roll along with what the newspapers call the ‘great wheel of the age.’* I knew you were a man who enjoys literature, so I mentioned a few famous literary works to demonstrate that I have similar interests and expertise. Conversely, had you been a prolific writer who opposed book reading, naturally I’d change my tune and tell you that I, too, considered it unnecessary to read books . . . yours excepted. Reading your books, after all, makes me feel that life is too short—how could I have the energy to read ancient tomes? I discuss inventions with scientists, archaeology with historians, and international affairs with politicians. At art exhibitions I talk about connoisseurship and at banquets I talk about the culinary arts. But that’s not all. Sometimes I instead talk politics with scientists and art with archaeologists; after all, they don’t understand a word I say and I’m happy to let them pass off my phrases as their own. When you play the zither to an ox, you don’t need to pick a good tune! At tea parties I usually discuss cooking on the chance that the hostess will pick up on my comments and—who knows—perhaps invite me to taste her own cooking a few days later. Having muddled by like this for tens of thousands of years I’ve gained something of a reputation in this world. Dante praised me as a refined thinker and Goethe spoke of me as worldly and knowledgeable.† One should be proud to have attained my status! But not me. On the contrary, I’ve grown more and more humble, often reproaching myself that, ‘I’m nothing but an underworld ghost!’* Like people who belittle themselves as ‘country folk,’ I worry that empty words are not enough to express my modesty, so I use my body as a symbol. A rich man’s gigantic sack of a belly signifies that he has ‘plenty in the bag,’ while a thinker’s bowed head and back arched into the shape of a question mark signifies his tendency to ask questions about everything. That’s why . . .” As he spoke, he extended his right hoof for me to see the extremely high heel on his leather shoe, “. . . the shape of my legs is so incredibly inconvenient†—it symbolizes my modesty and ‘inferiority.’5 I invented foot binding and high heels because I sometimes need to conceal my deformities, especially when I transform into a woman.”

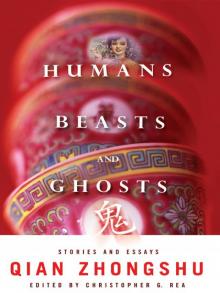

Humans, Beasts, and Ghosts

Humans, Beasts, and Ghosts